Source: The conversation

It sounds like great news for surfers, but homes, coastal infrastructure and unique wetlands are at increasing risk

A study, published today in Nature Climate Change, found a warming planet will alter ocean waves along more than 50% of the world’s coastlines. If the climate warms by more than 2? beyond pre-industrial levels, southern Australia is likely to see longer, more southerly waves that could alter the stability of the coastline.

Waves are generated by surface winds. Our changing climate will drive changes in wind patterns around the globe (and in turn alter rain patterns, for example by changing El Niño and La Niña patterns). Similarly, these changes in winds will alter global ocean wave conditions. Sea level rise can also change how waves travel from deep to shallow water.

Recent research analysed 33 years of wind and wave records from satellite measurements, and found average wind speeds have risen by 1.5 metres per second, and wave heights are up by 30cm – an 8% and 5% increase, respectively, over this relatively short historical record.

If the 2? Paris agreement target is kept, changes in wave patterns are likely to stay inside natural climate variability.

Some areas will see the height of waves remain the same, but their length or frequency change. This can result in more force exerted on the coast (or coastal infrastructure). About 40% of the world’s coastlines are likely to see changes in wave height, period and direction happening simultaneously.

Flooding from rising sea levels could cost US$14 trillion worldwide annually by 2100 if we miss the target of 2? warming. Changing wave characteristics will just make the damage worse in many areas.

Climate change – how are our coastlines fairing?

Source: CSIRO

The CSIRO are looking back to the period between 2011 and 2017 and found that climate-related events have had devastating impacts on key marine habitats.

These include kelp and mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs, some of which have not yet recovered, and may never do so. These findings paint a bleak picture, underscoring the need for urgent action.

Healthy kelp (left) in Western Australia is an important part of the food chain but it is vulnerable to even small changes in temperature and particularly slow to recover from disturbances such as the marine heatwave of 2011. Even small patches or gaps (right) where kelp has died can take many years to recover. Credit: Russ Babcock, Author provided

Timeline

During this period, which spanned both El Niño and La Niña conditions, scientists around Australia reported the following events:

2011: The most extreme marine heatwave ever occurred off the west coast of Australia. Temperatures were as much as 2-4? above average for extended periods and there was coral bleaching along more than 1,000km of coast and loss of kelp forest along hundreds of kilometres.

Seagrasses in Shark Bay and along the entire east coast of Queensland were also severely affected by extreme flooding and cyclones. The loss of seagrasses in Queensland may have led to a spike in deaths of turtles and dugongs.

2013: Extensive coral bleaching took place along more than 300km of the Pilbara coast of northwestern Australia.

2016: The most extreme coral bleaching ever recorded on the Great Barrier Reef affected more than 1,000km of the northern Great Barrier Reef. Mangrove forests across northern Australia were killed by a combination of drought, heat and abnormally low sea levels along the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria across the Northern Territory and into Western Australia.

2017: An unprecedented second consecutive summer of coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef affects northern Great Barrier Reef again, as well as parts of the reef further to the south.

Unique natural heritage areas affected

Many of the impacted areas are globally significant for their size and biodiversity, and because until now they have been relatively undisturbed by climate change. Some of the areas affected are also World Heritage Areas (Great Barrier Reef, Shark Bay, Ningaloo Coast).

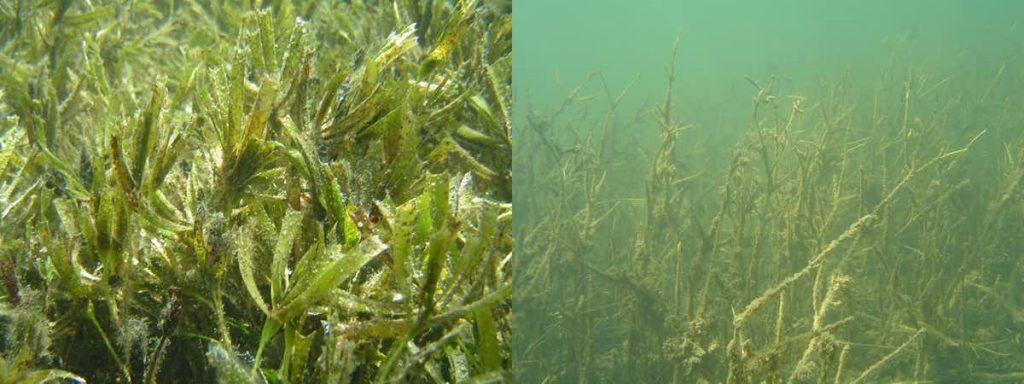

Seagrass meadows in Shark Bay are among the world’s most lush and extensive and help lock large amounts of carbon into sediments. The left image shows healthy seagrass but the right image shows damage from extreme climate events in 2011. Credit: Mat Vanderklift, Author provided

The habitats affected are “foundational”: they provide food and shelter to a huge range of species. Many of the animals affected – such as large fish and turtles – support commercial industries such as tourism and fishing, as well as being culturally important to Australians.

Recovery across these impacted habitats has begun, but it’s likely some areas will never return to their previous condition.

We have used ecosystem models to evaluate the likely long-term outcomes from extreme climate events predicted to become more frequent and more intense.

This work suggests that even in places where recovery starts, the average time for full recovery may be around 15 years. Large slow-growing species such as sharks and dugongs could take even longer, up to 60 years.

But extreme climate events are predicted to occur less than 15 years apart. This will result in a step-by-step decline in the condition of these ecosystems, as it leaves too little time between events for full recovery.

This already appears to be happening with the corals of the Great Barrier Reef.

What to do

Damage from extreme climate events occurs on top of more gradual changes driven by increases in average temperature, such as loss of kelp forests on the southeast coasts of Australia due to the spread of sea urchins and tropical grazing fish species.

“Ultimately, we need to slow down and stop the heating of our planet due to the release of greenhouse gases. But even with immediate and effective emissions reduction, the planet will remain warmer, and extreme climatic events more prevalent, for decades to come.” CSIRO

Mangroves at the Flinders River near Karumba in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The healthy mangrove forest (left) is near the river while the dead mangroves (right) are at higher levels where they were much more stressed by conditions in 2016. Some small surviving mangroves are seen beginning to recover by 2017. Credit: Robert Kenyon, Author provided