Tasmania’s vast ocean jurisdiction actually stretches as far south as the Sub-Antarctic zone. Nearly 1500 km South of Hobart is a ridge of volcanic rock rising off the sea floor. This area has rarely been visited by divers and was first dived only in 1978 by a team of scientists from the Australian Museum. My dive reports are based on this study. The only way most would be able to reach the island is by large cruise liner or ocean-going yacht. Previously the only way was through the good offices of the Australian Antarctic Division. They make 2-3 supply visits a year and leave usually 10-20 scientists. Unless you were a visiting scientist with impeccable physical and scientific credentials it was almost impossible to get a place on these Antarctic voyages as space is at an absolute premium. The island is managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, but is effectively run by the Antarctic Division who operate a permanent base there. There were plans to close the base, but a public outcry led to plans to completely rebuild it instead.

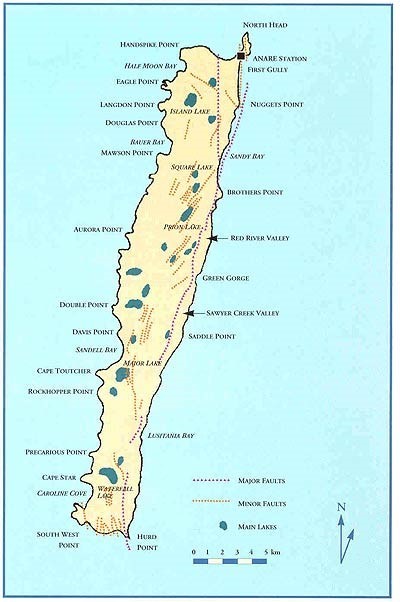

The island is oriented north-south and is 35 kms long and 5 kms wide. It is ringed by a narrow coastal shelf which rises steeply onto a high plateau of 250-300 metres containing many freshwater lakes. The west and south coasts are very rugged volcanic cliffs. The island appear to the observer to be very mountainous and green. The east coast has many pebbly beaches which are relatively sheltered although Easterly gales are also not uncommon.

The island is ringed by a relatively narrow area of shallow water before it drops away quickly into water over 4000 metres deep. The surface water temperature is 4-7 degrees Celsius while the air temperature is 3-7 degrees Celsius. Near the island the shallows are dominated by very thick stands of Durvillea Antarctica (Antarctic Bull Kelp). The kelp grows metres long and forms such a thick belt that it actually flattens out the swell that passes through it. Even seals and penguins have difficulty reaching the open sea. For obvious reasons Killer Whales patrol beyond this belt to catch the stragglers. Although Killer Whales are not known to attack humans, I don’t fancy testing that theory too often. It can be dived using normal scuba gear, but extra insulation is an obvious plus. The average tide fall is one metre while the average wave height is 1 metre on the West Coast and 0.8 metres on the East. The West Coast is particularly rough in the December to February Austral Summer.

Map via MESA

Marine life

The area lies close to the border between the Antarctic and Cold Temperate Zones and shares many animals with both biogeographic regions. About 4% of species are specific to the Sub-Antarctic zone, about 11% to Macquarie Island alone. The rest are common in either Antarctica or the Cold temperate zone. The islands are fairly barren in the shallows, but do have some very thick growths of algae, many invertebrate species, and a few interesting and unique fish species.

The west coast is very exposed and surgy down to 10-15 metres, the east coast slightly more sheltered. The shore is dominated by Antarctic Bull Kelp while a few species of invertebrate hang on in the shelter provided by the kelp fronds. In deeper waters some Macrocystis Pyrifera grows in less exposed areas, especially the east coast. A tufty 2 metre high species of brown algae dominates the east coast understory while large tufts of red algae live under its protection. Thick spongy mats of green algae are common in sheltered bays, while sea cucumbers, molluscs, starfish, sea squirts, hydroids, sponges, bryzoa and anemones thrive on rock faces. Rocks are often covered in pink coralline algae, chitons and limpets. Inshore Macquarie Island has no abalone, crays, brittle stars, crinoids, mussels, oysters or prawns. It does have a very large species of scallop which inhabits deeper areas of soft bottom.

There are only really 3 common inshore fish species at Macquarie Island. The small Spiny Plunderfish (Harpagifer georgianus georgianus) loves the shelter of boulders, while the Pigfish or Horsefish (Zanclorhynchus Spinifer) lives commonly in the sand under the kelp zone. The Magellanic Rock Cod (Paranotothenia Magellanica) is very abundant in the kelp zone and the juveniles are a major source of food for penguins. Many sub-Antarctic fish have, to put it bluntly, pretty ‘ugly’ large bony heads. A feature they seem to have in common with many Antarctic fishes. Superficially, many look a lot like temperate varieties of Scorpionfish.

Degree of Exposure

In 1984 the island had 273 days of strong wind and gales on 76 of those days. The winds are generally westerly and north-westerly. The climate is essentially the same all year round. The days are seven hours long in July and 17 hours long in January. The climate has been considered to be very similar to that of the South Island of New Zealand. The island is covered in almost constant cloud and fog on the west coast and humidity often reaches 90 per cent. the average cloud cover over the island is 83% and Macquarie Island receives an average of only 814 hours of sunshine a year.

Access

Because of the sudden boom in Antarctic wilderness tourism it is expected that the island will become more accessible in the near future. Since 1971 dozens of cruise ships have visited, but only about half put people ashore because of the bad weather and other complications. This popularity creates its own problems with serious concerns emerging about the impact of visits on the delicate ecosystem of the island. This has led to the need for a sound management plan and a few slightly alienating precautions such as tourist walkways and a book of regulations for visitors. There are duckboards to the two permitted landing sites at Sandy Bay and The Isthmus, but no roads. Landing is by permit only and tours can be arranged with a National Parks and Wildlife Service ranger as guide.

So if you were planning a dream adventure and had a permit here’s where to go and what it would look like.

The bottom in many places is covered in sea stars, hydroids and tunicates. Small Plunderfish are common under the boulders. In addition to all the small marine life the area is constantly buzzed by penguins,seals, diving seabirds and even whales at times. In depths greater than 10 metres thick Macrocystis forest thrives. A narrow band of bull kelp dominates the first few metres, but this soon gives way to green algae and encrusting coralline algae. The inter-tidal zone is swept free of life, while the edge of the sub-tidal zone is dominated by Antarctic Bull Kelp. The kelp is so thick it blocks out much of the light and tends also to flatten out the swell. The understory is made up of a low bushy brown algae Desmarestia Chordalis. The bottom is also dominated by Codium Subantarctica, a low felt-like green algae. Beneath this thick canopy a few marine animals find shelter in the low green algae that carpets the rocks. The kelp forest is apparently very scenic in good visibility.

The east coast of Macquarie Island tends to drop away more quickly and is deeper than the west coast. It is also more sheltered allowing a greater variety of delicate weeds and invertebrate life to thrive. The shallows are wave scoured and filled with gravel and sand. In deeper water there are some medium sized boulders that are a good place to see Pigfish and Plunderfish. The area is crowded with Elephant seals, Royal penguins and King penguins.

The rare shelter afforded by these boulders encourages invertebrate life. Sponges, anemones, starfish and sea cucumbers are common along the bottom. Colourful tunicates are particularly common. The deeper rock faces offer a little respite from the swell and large yellow sponges thrive on the rock walls.

Ok you are never going to get there, but its an interesting dream. Perhaps AAD can do a ‘virtual’ dive for us one day so we can see it without getting wet or cold.