In the maritime world, the entrance to Port Phillip Bay is the stuff of legends. It is described as “the most worrying and dangerous harbor entrance in Australia”. The Rip has claimed more than 50 ships, mostly in the late nineteenth century.

The Heads of Port Phillip Bay consist of a very narrow opening between Point Nepean and Point Lonsdale. Through here the massive Port Phillip Bay must empty and one square kilometre of water is shifted on each tide. This waterway is afflicted by big tidal currents (8 knots) and when the wind and swell work against the tide, huge standing waves. Some seamen have recorded tides of up to 12 knots, which was enough to make some slower steamers stand still in The Rip, even though their engines were at full power.

The entrance to Port Phillip is blocked by a shallow underwater rocky plateau. This was the ridge of rock that isolated Port Phillip Bay in prehistoric times, back when the sea levels were lower and the bay was just the flood plain of the Yarra River. The Rip was then just a little gorge where the river met the sea.

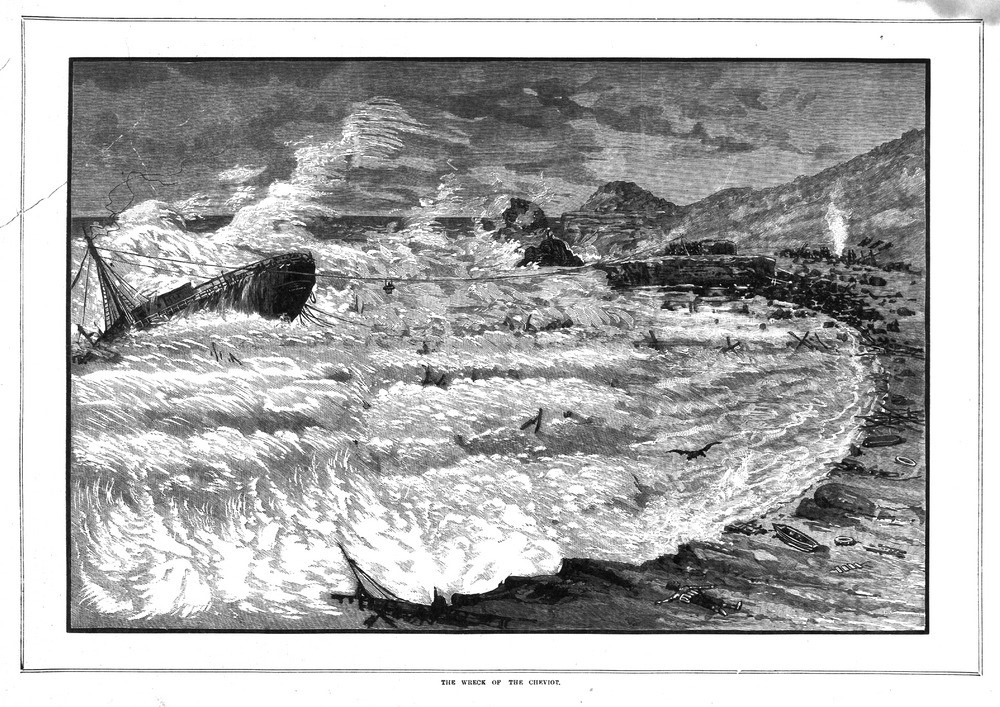

In the 1802, it was entered for the first time by European sailors. Lt Murray noted that The Rip was so rough it induced seasickness even among his seasoned crew. Back then it was a shallow and tide swept hazard only 28feet deep at its deepest part. Even in good weather the Rip caused vessels to pitch in the troughs and crests of waves, so they needed water at least four to five feet of water deeper than their draught. By the 1850’s the Ripbank was blocking the entrance to Australia’s new goldfields and the growing new city of Melbourne. The booming trade being done in the streets of Melbourne came at the cost. A series of tragic shipping disasters often brought about by the unique nature of the Ripbank.

In April, 1853, the “Sacramento”, bound from Melbourne to London with a large quantity of gold, went aground. The crew refused to take to the boats without the gold and narrowly escaped death. The sailing ship “Lightning” struck the main rock pinnacle in The Rip, and continued on its voyage to England apparently unharmed. Months later a large piece of rock was found jammed neatly into the bottom of the vessel. Many other ships were wrecked, some are now popular dive sites.

For 50 years the local port authority slowly chipped away at this rocky plateau. From 1900 everyone with an out-of –date stock of old explosives would find a ready buyer in the port authority, who used it to blast away at the Rip Bank and smash some of the larger rock pinnacles.

The blasting of the Ripbank attracted some controversy. In 1936 the Bass Strait ferry “Nairana” was struck by two giant waves as she entered the Heads in seemingly moderate weather (possibly a tsunami). Seas swept the decks, injuring several passengers, crushing one man’s head against a bollard. A family of three were washed overboard and never seen again. There were accusations that the blasting had exacerbated the waves in The Rip. This was rejected, it was always rough and earlier an Orient liner had lost a railing and several cabin doors in a similar incident.

By 1950, the port authority had doubled the depth to 43ft, more than the Suez Canal. The last big victim of the Rip was the freighter “Time”. She went aground early in the morning on August 27, 1949, after a breakdown in her steering-gear.

Now the Ripbank is still a source of wonder to divers. She still gets a lot of respect from local charter operators who often plan trips to the Ripbank but rarely get there. A dive on this fantastic underwater cliff can only be attempted on a slack water in very calm weather.

The wall boast large overhangs with bottom-dwelling (sessile) invertebrate animals clinging to the rocks in a blaze of primary colours. There are a lot of crayfish on the shelves here due to the low fishing effort. Three metre long seven gill sharks cruise along the wall. Dredging in the area more recently has damaged the bottom, but there is still plenty of life to be seen.