Mineral deposits, in the form of potato-sized nodules, cover wide areas of the world’s sea floor. Humans are interested in them but they are also extremely important for communities of deep-sea animals.

Most of the world’s deep ocean floor is soft sediment. However, there are large areas that also have these nodules scattered over the sediment surface. These nodules contain a range of important metals, including copper, cobalt and nickel.

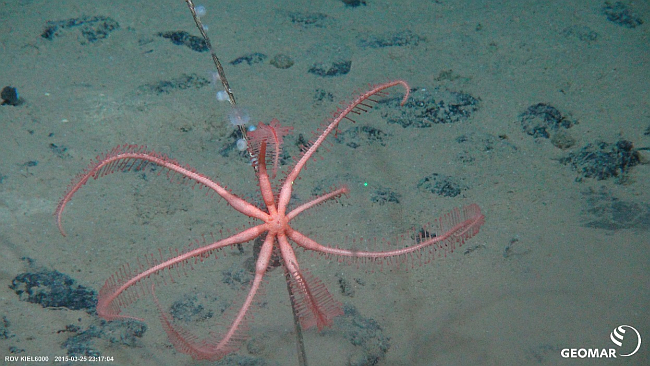

A new study shows nodule field are an important habitat and the dominant deep-sea animals change with nodule concentration. This study was based on high definition photos collected at the Clarion Clipperton Zone in 2015.

The implication of this is that successful conservation of deep-sea ecosystems in the event of nodule mining will require the preservation of areas with a full range of nodule concentrations, and not just the ‘low density’ areas that are least attractive to mining.

This Clarion Clipperton Zone in the central Pacific is one of the most important areas for nodules in the world. Yet, the living environment of this remote area is poorly known. The study area lies at an average depth of 13,000 feet, in complete darkness, crushing pressure and freezing temperatures. “The stereotype is that it’s like a desert. We’re finding that’s not the case at all.” The scientists saw 1,000 species, about 90% of them previously unknown and all of them in an area leased for mining exploration.

They also reported on the high impact and lack of recovery of fauna on 2 trawling tracks and experimental mining simulations up to 37 years old, suggesting that mining impacts may be long-lasting or even permanent.

The nodules are

formed when dissolved metal compounds in the sea water precipitate over time

around an object on the sea floor, a shark’s tooth or fragment of shell. In a

million years their size increases on the order of millimetres. Manganese

nodules can only grow in areas where the environmental conditions remain stable

over this kind of time scale with low sedimentation rates, a constant flow of

Antarctic bottom water, good oxygen supply and runny sediments. Some

researchers think that bottom-dwelling organisms such as worms must be present

in large numbers in order to constantly push the manganese nodules up to the

sediment surface.