Urchin Barrens

A normally benign little animal is munching its way through our marine environment in new and destructive ways. Research is just starting to uncover how and why.

An urchin barren is an area where urchins have eaten down the vegetation to the stage where it supports few of its original inhabitants and little in the way of a seaweed canopy. It’s a lousy place to fish, doesn’t support much marine life and makes for a pretty ordinary dive or snorkel.

Basically, an urchin does no harm to the environment while its populations are stable and densities are relatively low. Then when an environmental change occurs, urchins can build up in numbers and starting stripping the bottom. They start to thin out the weed regrowth, working on the easy to eat young seaweed first. When the larger and harder to eat old plants get ripped out by storms, there are no young plants to replace them. One minute the reef looks OK to the untrained eye, the next day there is bare rock.

Environmental changes that trigger this effect could be the loss of predators in the area, or abnormally good breeding conditions. Climate change is thought to alter the breeding conditions, and overfishing can affect predator numbers.

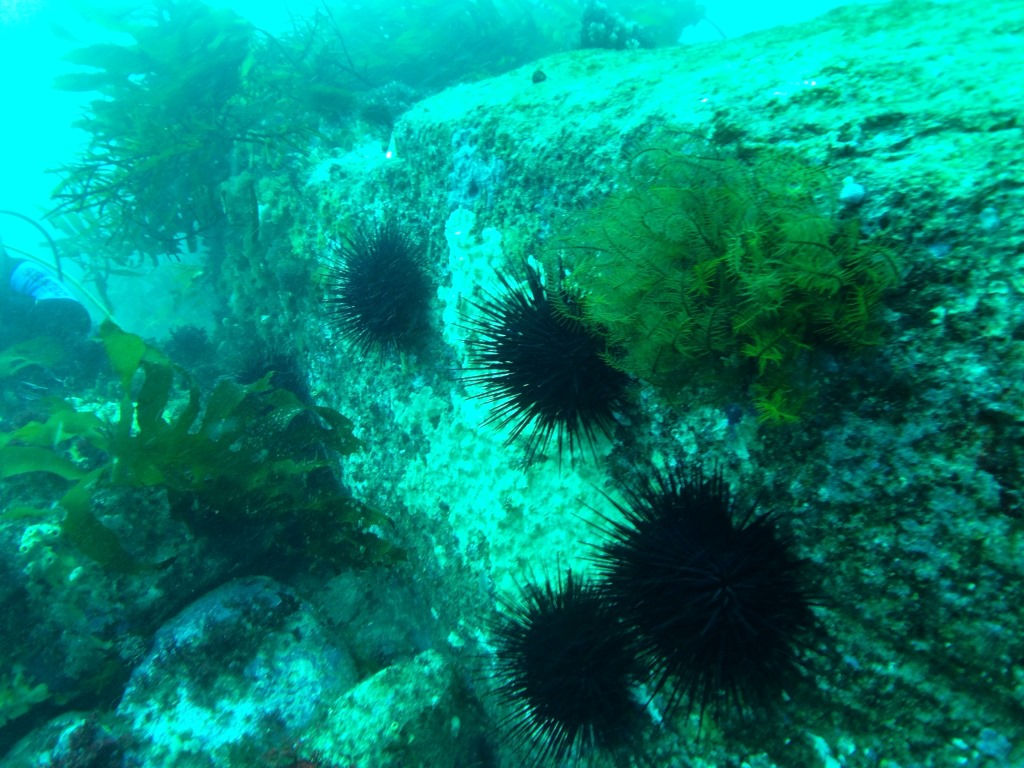

Black urchin barrens

In Tasmania we have heard a lot about NSW long-spined urchins, also called black urchins, (Centrostephanus Rogersii). They are native to NSW, but they have been extending their range, and have infested the East Coasts of Victoria and Tasmania. They are extremely voracious and can graze an area down to absolutely bare rock over huge areas. St Helens has been heavily damaged by this urchin activity and few areas in the 15-40M range, from the Gardens to St Helens Island, still have good marine life.

Spots of urchin damage are now appearing all down the coast. This development is impacting on fisheries already and is stripping vast areas of its natural marine life. This problem is believed to be caused by overfishing of large crayfish and warming oceans that are encouraging breeding further south than normal.

Native urchin barrens

Fewer people realise that the Tasmanian native or purple urchin (Heliocidaris Erythrogramma) can also cause extensive barrens. Oddly these mainly appear in sheltered areas. These barrens also tend to be smaller and less bare than black urchin barrens. These natives can still be a big problem where they eat out environmentally sensitive areas like giant kelp beds, or rare Handfish habitat.

They also create opportunities for newer vagrants to get established, like the introduced Japanese pest seaweed Undaria Pinnatafida. Although no-one has good records, the native urchin barren areas may be growing.

New Research

Black urchins have been studied quite a bit lately. FRDC funding has allowed a major new study to be carried out into native urchin barrens. Scientists Scotty Ling, Sam Ibbott and Craig Sanderson have been studying barrens for a long time. They picked two barren reefs on the East Coast of Tasmania for study and these held urchin densities of 4-6 per metre which is a density quite common on the East Coast. Seaweed canopy cover in these areas was down to only 5% of the bottom. Fences were erected around patches of reef to ensure the urchins didn’t get in or out as urchins do like to roam about during the year. They removed the urchins in each plot and divers measured how the reef recovered in each of the plots over the next two years. The way the native urchins feed on the reef depends on where the reef is, and how much alternative food the urchins have to feed on. Numbers are important, but not the whole story. The native urchin will clear off the reef only as a last resort when the population gets too high for the local supply of drift algae. These damaged areas can be fixed by controlling the population of urchins, but it seems like you have to try to get in early. Longterm and very bare native urchin barrens may prove to be very difficult to rehabilitate.

Another ambitious urchin barren research project at Elephant Rock on the East Coast of Tasmania has ended, with surprises for everyone. Earlier research had identified rising sea temperatures and declining stocks of large lobsters as the main causes of the problem. Ideas to fix it ranged from smashing urchins by hand, commercial harvesting for seafood, to introducing maximum lobster size limits. The project was trying to see if these were cost effective options to minimise the impact of C. rodgersii. Abalone divers offered to hand clear urchins from their favourite fishing spots. Fishermen caught large numbers of huge lobster for transplanting at Elephant Rock in St Helens, where a ‘no fishing’ zone was declared. A new business in St Helens also offered to trial export shipments of urchin roe to Asia.

The answer is that there are no easy fixes. The problem is so big that it’s already too late for physical removal to ‘fix’ the problem. It only helped in a few very tiny patches.

Translocation of large predatory capable lobsters (>140 mm long in the carapace) to the reserves demonstrated that large lobsters live happily on extensive barrens. Barrens habitat will support large populations of large lobsters. The big lobsters had a significant impact on small incipient barrens and they declined rapidly in size, but their greedy eating still made no impact on the really big barren areas.

Controlling urchins by rebuilding populations of large predatory rock lobsters can keep the problem from getting worse, and rehabilitate some of the moderately damaged areas. The answer is immediate prevention rather than a later cure. Once the barrens expand and become massive, they are likely to stay marine life (and marine seafood) free deserts for a very, very long time.

Controlling urchins by rebuilding populations of large predatory rock lobsters can keep the problem from getting worse, and rehabilitate some of the moderately damaged areas. The answer is immediate prevention rather than a later cure. Once the barrens expand and become massive, they are likely to stay marine life (and marine seafood) free deserts for a very, very long time.

In short, the long-term answer is the same as for many problems in the marine environment. It probably doesn’t need a man-made bandaid. Fix distortions in the environment like climate change and stop overfishing.