Recently

corals in Lord Howe Island Marine Park began showing signs of bleaching. The

145,000 hectare marine park contains the most southerly coral reef in the world.

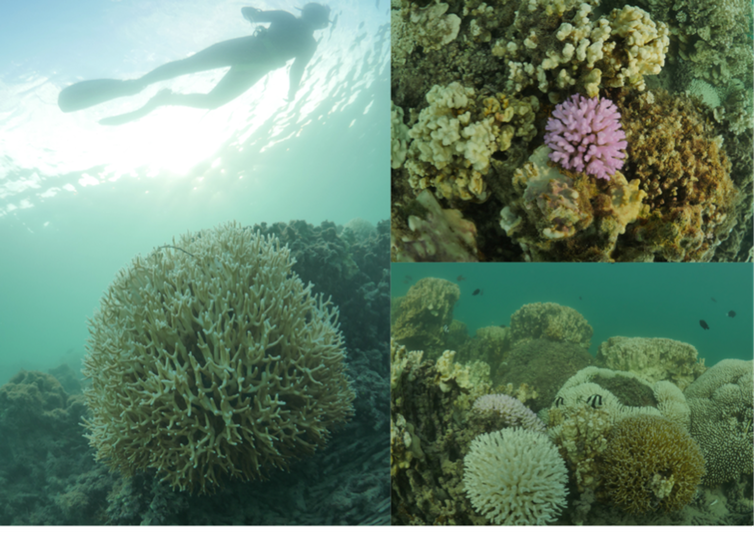

Sustained heat stress has seen 90% of some reefs bleached, although other parts

of the marine park have escaped largely unscathed.

Lord Howe Island was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982. It is the coral reef closest to a pole, and contains many species found nowhere else in the world.

Research found severe bleaching on the inshore lagoon reefs. Of the six sites the team looked at, five of them were impacted by coral bleaching. One specific site that was the most severe saw 92 per cent bleaching.

However, bleaching is highly variable across Lord Howe Island. Some areas within the Lord Howe Island lagoon coral reef are not showing signs of bleaching and have remained healthy and vibrant throughout the summer.

One surveyed reef location in Lord Howe Island Marine Park is severely impacted, with more than 90% of corals bleached; at the next most affected reef site roughly 50% of corals are bleached, and the remaining sites are less than 30% bleached. At least three sites have less than 5% bleached corals. There are also corals on the outer reef and at deeper reef sites that have remained healthy, with minimal or no bleaching.

In parts of the lagoon areas the water can be cooler, due to factors like ocean currents and fresh groundwater intrusion, protecting some areas from bleaching. Some coral varieties are also more heat-resistant, and a particular reef that has been exposed to high temperatures in the past may better cope with the current conditions. For a complex variety of reasons, the bleaching is unevenly affecting the whole marine park.

There is evidence that some corals are now dying on the most severely affected reefs.

This is now the third recorded bleaching event to have occurred on this remote reef system. The last was in 2010. Bleached and partially bleached coral cover exceeded 90% at Sylph’s Hole and Comet’s Hole in the lagoon during March 2010, with less extensive and patchy bleaching at other reef sites around LHI. Pocilloporid corals (Stylophora, Pocillopora and Seriatopora) and Montipora spp. bleached more extensively than other corals. Some bleaching-related coral mortality was evident during March 2010, with up to 25% of corals at Comet’s Hole having partial or complete bleaching-induced mortality.

Essentially, the algae which feeds coral reefs and gives it its colour can become toxic. In turn, the coral spits it out. “Bleaching is essentially the coral skeleton. “But that doesn’t mean the coral is dead, it just “has a weakened immune system”, Tess Moriarty said. “In these events if the heating goes on for too long, it can see mortalities. So we can see mass mortalities after severe coral bleaching events.”

When corals die, other forms of algae thrive. It blooms and eats away at coral skeletons, leaving marine animals without any shelter and food once provided by coral reefs.

UNESCO World Heritage regions, such as the Lord Howe Island Group, require urgent action to address the cause and impact of a changing climate.