Blackbirding

Ask most people on the street and they would say that Australian hasn’t been directly involved in slavery, at least organised slavery in the sense of kidnapping and selling people and forcing them to work. But that isn’t true. The forced labour practices in the South Seas, known as “blackbirding”, are a stain on our history.

In the mid nineteenth century, a shortage of labour in the new Queensland sugar industry led to attempts to recruit labourers in the South Pacific. The locals usually weren’t interested, so various forms of trickery and coercion were used to get them on board, then they were locked in the holds.

The working conditions in Queensland and northern NSW varied depending on the farmer, but they were mostly poor, with treatment varying from neglect to downright slavery. After being delivered to a plantation, a blackbirded islander could in theory expect to work for three to five years for six days a week before being handed a tiny sum of money – ten pounds was a typical figure – and being sent home on a ship. In practice, many labourers died of neglect or overwork before finishing their contracts. Those who lived long enough to leave their plantations were often placed on a ship and dropped on the nearest convenient island, where they faced being ostracised or killed by locals. Labourers who deserted their plantations were hunted down and beaten.

There is still some argument about whether or not it was slavery in the classic sense, but the Anglican Bishop of Melanesia ridiculed the notion that islanders had signed fair contracts with the blackbirders,

“I do not believe that it is possible for any of these traders to make a bona fide contract with any of the natives of the northern New Hebrides, Banks and Solomon Islands. I doubt if any one of these traders can speak half a dozen words in any one of the dialects of those Islands; and I am sure that the very idea of a contract cannot be made with a native of those islands without a full power of communicating readily with him. More than ten natives of Mota Island have now been absent nearly three years. The trader made a contract with them by holding up three fingers. They thought that three suns or moons were signified. Probably he was very willing that they should think so, but he thought of three years.”

Island missionaries were the main European voices actively reporting on the excesses. Captain Rees was charged with landing his vessel at Malicolo, New Hebrides (Vanuatu) with the sole intention of killing South Sea Islander people. He also openly planned to abduct and assault a girl from Port Resolution, Tanna.

His armed boat’s crew had seized the chief and refused to release him except in exchange for the chief’s daughter Naxuyi. Naxuyi was taken on board Lewin’s ship, the Spunkie, and assaulted. A few days later, on 12th January 1869, Lewin was charged in the Brisbane Police Court, with a criminal assault on this Tanna girl. “Native witnesses told how the girl had been brought aboard and thrust into the hold amongst the native men and how she had been followed by Lewin, from whom the blackbirds fled in terror.” It was decided that there was not enough evidence to go to a jury and Lewin was discharged.

Labour schooner “Fearless”

When the Daphne was captured operating outside the law, an RN officer noted “She was fitted up like an African slaver, minus the irons, with one hundred natives on board. They were stark naked; not even a mat to lie upon, the shelves were just the same as might be knocked up for a lot of pigs, and yet the vessel was inspected by a Government Officer in Queensland.”. Captain Palmer arrested the ship’s officers and put a prize crew on the Daphne.

By the end of the 1860s at least fifty ships were working full-time to supply the plantations of Queensland and Fiji with labourers. In addition, a handful of ships supplied labour to the smaller cotton farms which had been established in Tahiti and on Samoa. In 1870 the little island of Fortuna in the New Hebrides alone received more than forty different visits from blackbirders, and lost nearly half its population of nine hundred. In an account of blackbirding published in 1888, a former slaver described the devastation that the trade brought to one island:

“After travelling

about two miles, we came right in front of a long clearing, and sticking out of

it were a lot of what we took to be black poles. The skipper, as soon as we saw

them, swore worse than ever, and said “We’ll get no men in this place;

somebody has been here before us’…there was an awful stink, which grew stronger

and stronger…Here, there, and everywhere – in twos and three, and bunches,

with limbs all twisted and stiffened, blocked and blistered, in the scorching

sun – were the bodies of a lot of natives, men, women, and children…In the

middle of them was a drove of wild pigs, scarcely able to move after their

horrible feast. I began to think I had had quite enough of blackbirding… “

By 1871 blackbirding had brought chaos to large parts of the western Pacific.

Across the New Hebrides and the Solomons, missionaries, whalers and legitimate

traders as well as blackbirders were being attacked by people angry at the

depopulation of their islands. Coley Patteson quickly noticed the effects of

blackbirding on Melanesia. The Bishop had once been welcomed by large peaceful

crowds on his journeys through the islands, but after the beginning of

large-scale blackbirding he found shorelines and villages suddenly deserted.

When Patteson did make contact with islanders, he frequently found them

hostile; not unreasonably, they associated all white men with blackbirding.

Moral outrage led to tighter regulation backed up by Royal Navy patrols. Wealthy sugar plantation owners ensured that governments never totally stopped the trade, and prosecutions against shipowners usually failed. By the 1880s, the industry had become more benign, although there were still excesses. More islanders were coming voluntarily and being returned at the end of harvesting. “White Australia” racism led to the forced removal of most remaining “Kanakas” by the end of the century.

Over 100 vessels operated in the late 19th century transporting approximately 60,000 South Sea Islanders to and from Queensland to work as labourers in establishing the sugar cane industry.

QLD – The Foam

In February 1893, the schooner Foam was carrying 84 South Sea Islanders back to the Solomon Islands. She was wrecked on Myrmidon Reef near Townsville. When the ‘Christina Gollan’ reached the vessel it found the ‘Foam’ lying on its port side, approximately two-thirds of the vessel under water at low tide, the starboard quarter just visible above the water. All those on board were saved. Fittings from the vessel were recovered before the vessel was a total loss. Ninety years later in May 1982, the wreck was discovered in 6 metres of water. Items like the armbands in the photo, have been found on the wreck and are helping archaeologists discover more about these vessels and the lives of those on board. The ‘Foam’ was originally built as the ‘Archimedes’ and renamed the ‘in 1892.

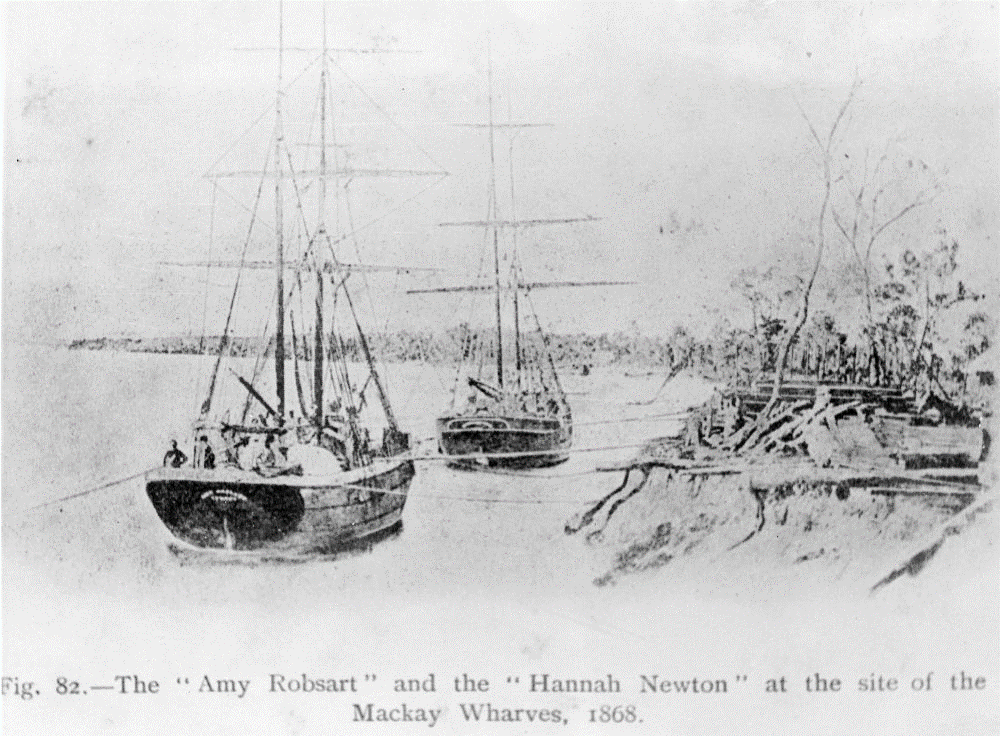

Tas – Amy Robsart

The earliest recruiting ship to be photographed was Amy Robsart in 1868. This 72-ton brigantine that made two trips in the labour trade in 1870, carrying 60 to 70 labourers. Conditions must have been very basic on board as the ship was quickly converted from a coastal trader

Amy Robsart was built at Brisbane Water, New South Wales, by Henry Robert Cox in 1865 for the trade between Sydney and the rivers of northern New South Wales. Amy Robsart had traded extensively around all of the Australian colonies, New Zealand and some of the South Pacific Islands.

She arrived in Hobart from Western Australia in 1875, with a cargo of jarrah and the wife and family of Governor Weld, who had then just been appointed to the Governorship of Tasmania.

On 28 February 1883 the 75 ton brigantine Amy Robsart was on a voyage from the Don River to Macquarie Harbour with a cargo of timber for the Cliff Tin Mining Co at Trial Harbour when a heavy gale brew up,

“She would have cleared the land right enough only for a heavy sea striking her forward, carrying away her bowsprit. I do not recollect to have ever seen it blow harder, or the sea to got up quicker. The vessel drifted ashore, and we could not help her. This has been the narrowest shave for life I ever had. You may think it was given up when we all shook hands and said good-bye. As luck would have it, the vessel got in behind some rocks… The cook had his skull fractured, and I got my back hurt; otherwise we are all well”

The brigantine drifted

ashore near Conical Rocks and was a total loss.